The Cape Breton Wireless Heritage Society

The First Transatlantic Wireless Service and its Stations in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

A Brief History

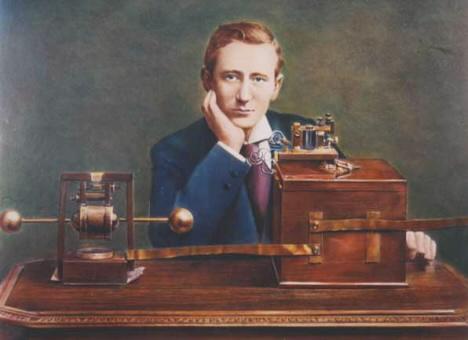

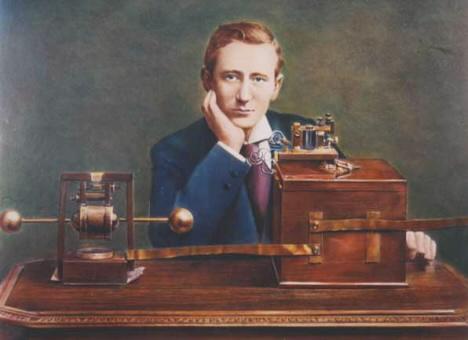

Many people contributed to the development of wireless communications, but the best known is Guglielmo Marconi. In1895, at the age of 21, Marconi demonstrated the transmission and reception of wireless signals over a distance of about one mile on the family estate near Bologna, Italy. He moved to England in1896, and set up a company there in1897 to manufacture and lease wireless equipment.

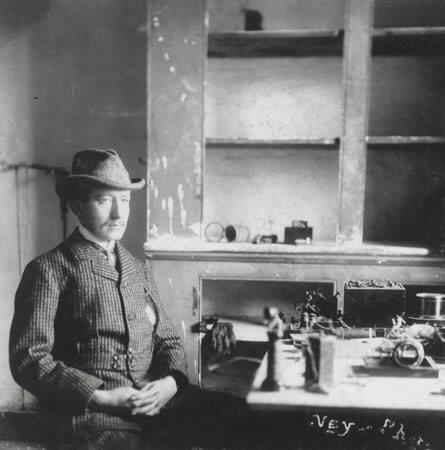

Marconi and his radio apparatus after arriving in England in 1896.

This was wireless before the age of electronics. The radio transmitter utilized the electrical impulses produced by a high voltage spark, and was called a spark transmitter. The receiver detected the radio signal with a primitive device called a coherer, but it had no means of amplifying the signal electronically. Despite its simplicity, the system worked, and was gradually developed to provide reliable wireless communications over distances of a hundred miles or more. Wireless was especially useful at sea, where distress signals from sinking ships saved thousands of lives.

The next goal for Marconi was worldwide radio communications, and the first step was to bridge the Atlantic Ocean. In December, 1901 Marconi received a radio test signal at St. John's, Newfoundland that was transmitted by his station in Cornwall, England.

Marconi and his assistants at St. John's, Newfoundland, raising a kite to support his receiving aerial wire.

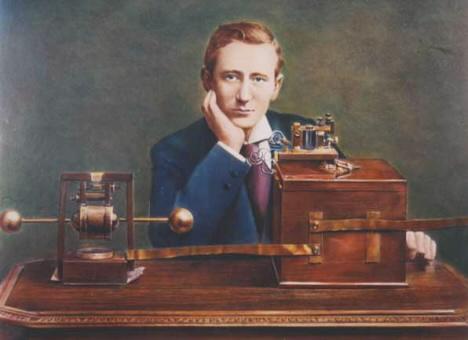

Marconi and his receiving apparatus in a former hospital building on Signal Hill at St. John's, Newfoundland in December, 1901

The company that operated the transatlantic telegraph cable threatened Marconi with legal action if he continued his experiments because they held a monopoly on telegraph operations in Newfoundland. Rather than endure legal delays, Marconi left Newfoundland and sailed to North Sydney, Cape Breton. There alert Canadian officials persuaded him to build a permanent station in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. In 1902 he built a radio station at Table Head in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia for transatlantic communications. In December of that year he transmitted Morse code messages from this station to his station in Cornwall.

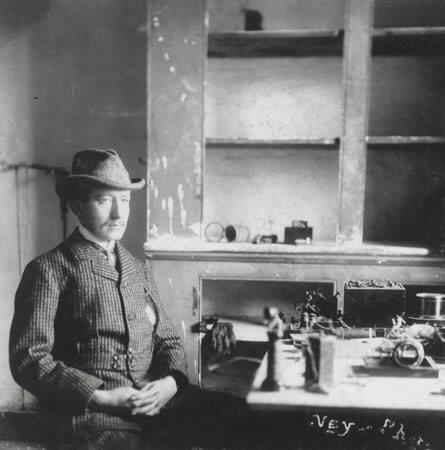

Marconi's transatlantic wireless station at Table Head in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. The four 200 foot wooden latticework towers shown supported an inverted pyramid of antenna wires that do not show up in the photograph. Glace Bay, originally Baie de Glace, means ice bay. The photograph shows why.

Communications between Glace Bay and Cornwall proved unreliable, and only possible after dark, so between 1905 and 1907 Marconi and his company built large new stations on both sides of the Atlantic. These stations were at Clifden, Ireland, and just south of Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. The latter station became known locally as Marconi Towers The two stations operated on wavelengths of thousands of metres, and were the most powerful radio stations in the world.

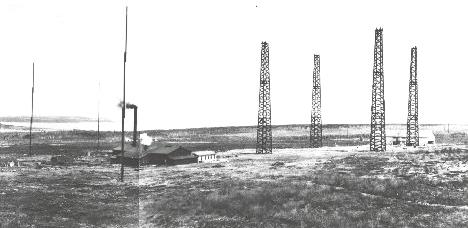

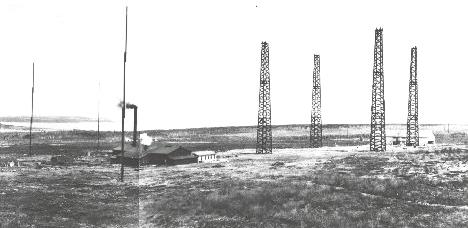

The Marconi Towers station circa 1909. The building with the smoke stack is the power house that generated electric power for the station. The transmitter building is at the right, behind the wooden latticework towers. The antenna was a circular umbrella of wires that do not show up in the photograph. It was 2200 feet in diameter, and was supported by the four wooden towers and outlying wooden poles, some of which appear in the photograph. The town of Glace Bay is in the left background.

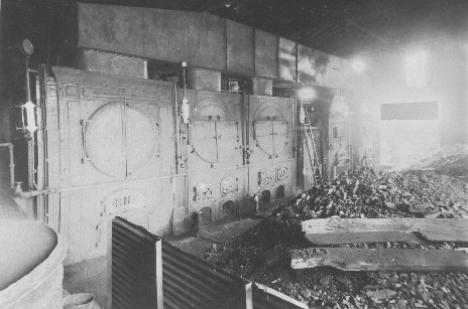

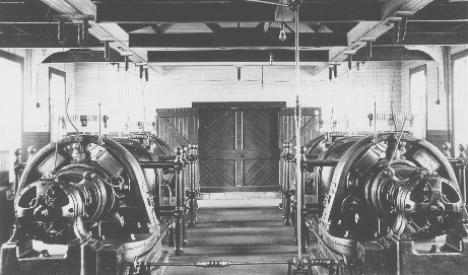

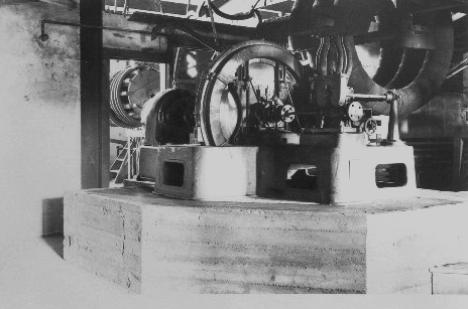

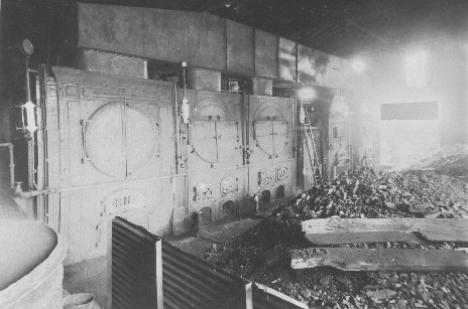

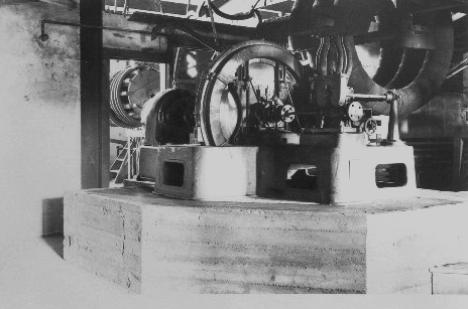

Coal fired boilers in the power house at Marconi Towers produced steam for the main steam engine and alternator.

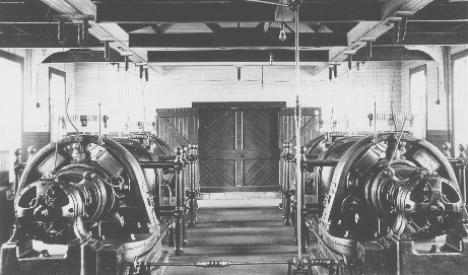

Three of these five kilovolt DC generators connected in series powered the spark transmitter at Marconi Towers. The fourth was a spare.

The rotary spark discharger was the heart of the spark transmitter at Marconi Towers. The three large ring shaped structures in the background at the upper right are the three turns of the primary coil of the antenna transformer that transferred electrical energy from the spark to the antenna high overhead.

The technology was much like that used in the original experiments, but scaled up to gigantic proportions. Transatlantic communication was successful both day and night, and a regular commercial service between Marconi Towers and Clifden opened officially on October 17, 1907. In succeeding years it was followed by competing services operated by other companies and countries, spanning the oceans of the world, and leading to the worldwide wireless network that we take for granted today.

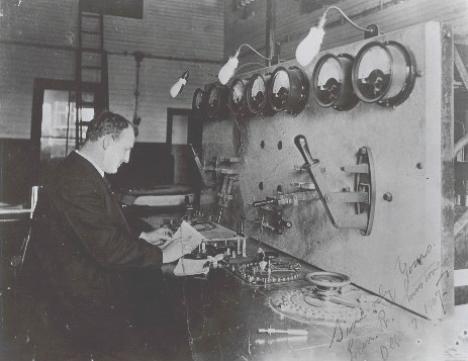

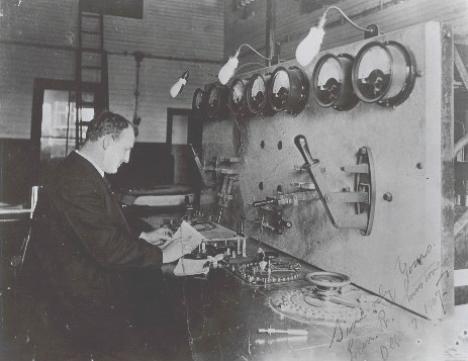

Chief operator, L. R. Johnstone, transmitting messages in Morse Code to Clifden, Ireland, on the official opening day of the transatlantic service, October 17, 1907.

Operator James Holmes receives messages at Marconi Towers from Clifden, Ireland in 1907, while Marconi looks on.

Initially the stations at Marconi Towers and Clifden were limited to one-way-at-a-time transmissions, either east-to-west or west-to-east. Telegraphers called this a simplex system. This limitation was due to the fact that the receivers, which were at the same locations as the transmitters, could not function while the transmitter was operating. When business justified it, the system was upgraded to a simultaneous two-way or duplex system by the addition of dedicated receiving stations at Letterfrack, Ireland and Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. The duplex service began in 1913.

The Marconi transatlantic receiving station at Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. The main operations building is the one-storey building in the middle of the photograph. The other buildings are staff residences. The six 100 metre high steel towers that supported a one kilometre long receiving aerial wire are in the right background.

The land lines room at the Louisbourg receiving station circa 1913. These operators transferred messages received from Clifden, Ireland to North American telegraph networks. The reverse was also done here. Messages received via the telegraph lines were relayed overseas by the transmitter at Marconi Towers, which was connected to Louisbourg via landlines.

In the next few years, the operation of these stations was improved by the introduction of vacuum tubes. In the receivers, tubes amplified the faint signals from overseas thousands of times. In the transmitters, tubes replaced the impulsive signal generated by the spark with a smooth continuous wave. Tubes of this type ushered in the age of electronics.

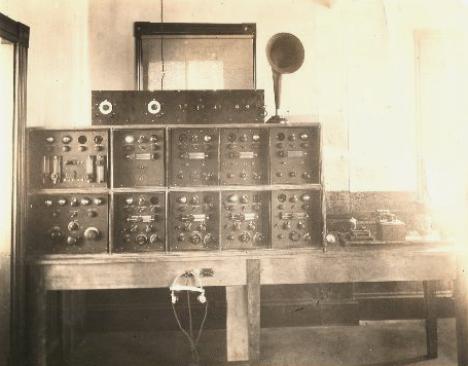

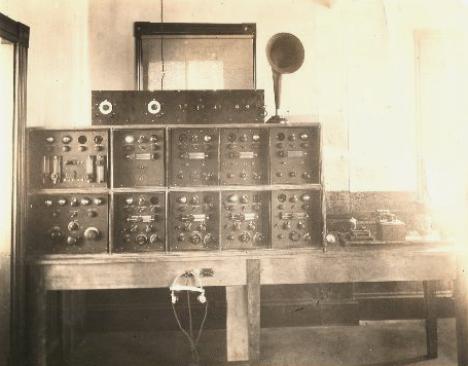

Vacuum tubes became readily available after World War 1. Tubes amplified the received signals thousands of times, even enabling signals from overseas to be heard on a loud speaker, like the antique on on top of the receiver.

After World War 1, racks of large silent vacuum tubes like these replaced the noisy spark in the transmitter at Marconi Towers. The smooth continuous wave, which replaced the impulsive damped wave produced by the spark transmitter, allowed transmission of the human voice. Nevertheless, Morse code still was the preferred mode of transatlantic communications. More importantly, continuous wave generated a more precise transmission frequency, enabling better separation from other signals.

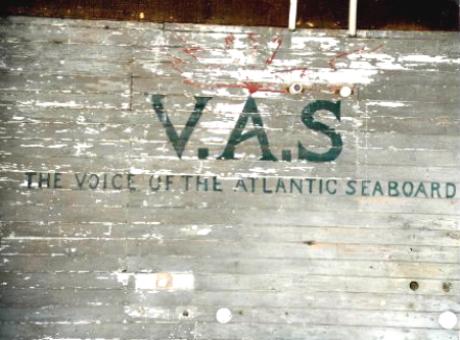

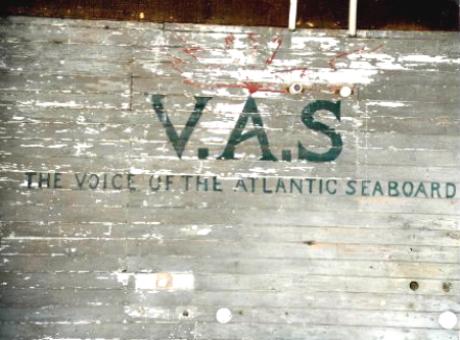

The station at Clifden was destroyed by Irish rebels in 1922, and its service was taken over by a newer long wavelength station at Caernarfon (Carnarvon) in Wales. In the 1920's the advantages of short wavelengths for long distance radio communications were discovered, and were investigated systematically by Marconi. In 1926 the long wave transatlantic service with its Cape Breton stations was shut down and was replaced by a short wave service between London and Montreal. The receiving station at Louisbourg was dismantled, but the station at Marconi Towers remained in operation until 1945. It performed various services, including long range communications with ships in the North Atlantic, and broadcasting marine weather information using the call letters "V A S".

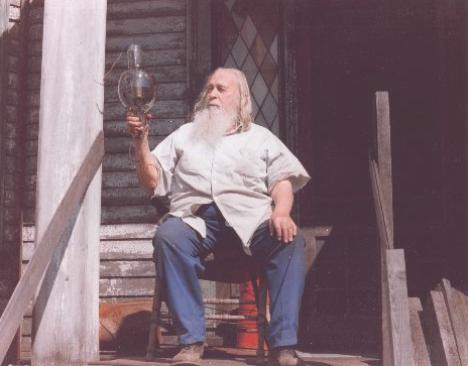

In 1945 the Marconi Towers property was bought by Russell Cunningham, a local citizen, and it still is owned by the Cunningham family. About all that is left of the station today is the house that Marconi and his new bride lived in while the station was being built, and the derelict remains of the transmitter building.

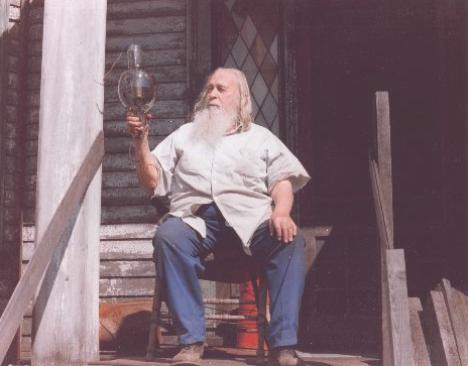

The late Russell Cunningham, circa 1984, holding a vacuum tube from the Marconi Towers transmitter. He bought the station property from the Marconi Company in 1945, and thanks to him and his family, the property has remained largely intact.

This is the house that Marconi and his new bride Beatrice lived in circa 1905 - 1907 while the Marconi Towers station was being built and tested. After the station opened for business it became the managers residence, and remained so until 1945. It is now the home of Douglas and Diane Cunningham and their family, who have maintained it in reasonably authentic condition.

This is the remains of the central part of the transmitter building at Marconi Towers. The transmitter was connected to the great antenna array via wires that passed through holes in the plate glass window in the roof.

After vacuum tubes came to Marconi Towers, voice broadcasts for mariners were made using the call letters "V A S". The station was nicknamed the Voice of the Atlantic Seaboard. Today, this logo remains on the inside of the south wall of the transmitter building.

The Louisbourg station site is located in the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park. All that remains of it are the concrete foundations of the antenna towers and the concrete guy wire anchors. The site of the station at Table Head in Glace Bay is called the Marconi National Historic Site. It is operated by Parks Canada, and contains an interpretive centre that is open to the public in the summer months.

The interpretive centre at the Marconi National Historic Site at Table Head in Glace Bay, the location of Marconi's first transatlantic station.

For more details see:

Marconi's Three Transatlantic Radio Stations In Cape Breton

For a biographical account of Marconi's work in Cape Breton, read the book:

"Whisper In The Air - Marconi: The Canada Years"

by Mary K. Macleod, 1992, Lancelot Books, Hantsport, Nova Scotia ISBN 0889995184

Return to Home Page and Contents

First uploaded to the WWW: 03 December 2006